E: Much of the discontent around this year’s very white, very male-oriented Oscar nominations has focused on the all-male slate of directors, and particularly on Greta Gerwig’s exclusion from the list. Fans of the film from Entertainment Weekly to Trevor Noah keep asking “Did Little Women direct itself?” Of course, she’s not the only one – exclusion is inevitable when there are nine Best Picture nominees and only five Directing nominees, including both Gerwig and her husband Noah Baumbach, who each helmed Best Picture nominees that received 6 nominations over all. But so few women achieve this honor (and none for the second time, as Gerwig was poised to) that it sticks out.

What strikes me most about the whole situation is this: comment after comment on these article asked, well, what if the five directors chosen were just the best ones this year? Why, the public seems to wonder, do you have to make a big deal about one nomination? Gerwig isn’t entitled to a nomination just because she’s a woman. She got legitimately beat, and now the political correctness police are crying foul.

And that is what gets me, because the whole issue with the 2020 Oscars is not individual snubs but the pattern those snubs betray through history and context. If you don’t pay attention, it might seem like hey, it’s just one nomination. It’s just this year. It’s all subjective. Who cares? But ah, context.

So. Let’s look at it all. Let’s talk about some context.

And to do that let’s admit that the entire point of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and of that group creating the Oscar award way back in 1929, has always been to sell more movie tickets, with the lesser goal of establishing film-making as an art form to be celebrated rather than mocked by intellectual elites. The nominated films are chosen by industry professionals, and are supposed to represent the height of their craft — but winning an Oscar has never been like winning a footrace. There’s a subjective groupthink involved. It’s always reasonable to question the preferences of Oscar voters, because it’s always been a popularity contest. What’s worrisome about this year’s Oscar’s has been worrisome for quite some time. As more opportunities arise for women and artists of color, AMPAS shifts what it deems award-worthy, making sure for each step forward, there’s at least one corresponding step back.

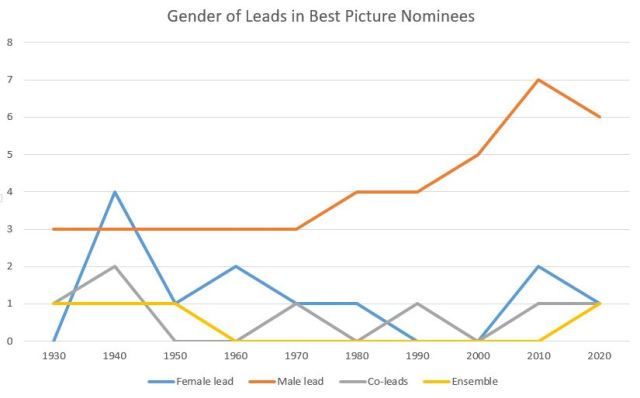

Let’s take a look back, to the first year of every decade, and see what sorts of movies Oscar has favored in the past, and whether that tells a different story than what Oscar favors now.

1930

Best Picture Nominees: Alibi, Hollywood Revue, In Old Arizona, The Broadway Melody, The Patriot

As readers of this blog know, I grew up in a family of cinephiles, but the only one of these I’d even heard of is pioneering talkie-musical (and winner) The Broadway Melody, and that’s largely because it’s referenced in Singing in the Rain. But it’s worth noting that the five nominees include a musical romance, a gang melodrama about a man hiding his criminal life while married to a policeman’s daughter, a variety show featuring the some of the greatest male and female stars of the day, a western (the first talkie filmed outside) and a largely silent historical melodrama about Russian court politics.

All five movies seem to have had mostly white casts and white male directors, and the four with actual plots seem to have made male main characters, though with major involvement from female co-leads or strong supporting female characters. Related note: Later in the 1930s, Merle Oberon was nominated for Best Actress; since she’s partly Maori, some claim her as the first (and only) Asian Best Actress nominee.

You can see from the descriptions, however, that there’s great variety in the type of film nominated. It’s worth noting that the winner (Broadway Melody) was also the top box office earner of the year. In Wings, the very first Best Picture winner in 1929, two fighter pilots vie for the love of top-billed star Clara Bow. In the 30s, western Cimarron and romcom It Happened One Night each had male and female co-leads, while Cavalcade and Grand Hotel won their years as ensemble stories with strong female leads.

1940

Best Picture Nominees: Dark Victory, Gone with the Wind, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, Love Affair, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Ninotcha, Of Mice and Men, Stagecoach, The Wizard of Oz, Wuthering Heights

Welcome to the Golden Age of Hollywood! So many classics! So many best picture nominees! We have, in turn, a melodramatic romance about a woman dying of cancer, a romantic epic that creates the myth of the glorious antebellum South, the moving story of a teacher’s life, another romance about a disabled woman (though the story is better known now from its later incarnation as An Affair to Remember), an inspirational political film, a romantic comedy about a Russian agent seduced by capitalism, a bleak and gritty literary adaption, a western heist flick, one of the most famous fantasy films of all time, and a romantic costume drama. So many genres! So many stories that still capture the imagination of movie goers! The winner, Gone with the Wind, was not only the box office champ of its year, but when adjusted for inflation, is the domestic champ of all time. The main character is a woman.

Of the ten films, 4 have female leads and 2 have male and female co-leads, making the genders essentially equal in representation. Of Mice and Men and Mr. Smith Go To Washington each have casts composed largely of men, but at least one significant and substantive female role. All the directing nominees are white men, as in 1930, but again we see a tremendous variety of genre (comedy, drama, melodrama, romance, adventure) as well as films that represent both men’s and women’s stories.

Interestingly, 1940 and 2020 have the same number of nominees of color — 19 white actors and 1 black woman who plays a slave. A notable difference? In 1940, Hattie McDaniels became the first African American to win an Oscar, whereas Cynthia Erivo is unlikely to take home a statuette. (Note: Jose Ferrer received a nomination during the ’40s, one of the very few people of color to appear on Oscar’s rolls then.) Other classic movies from 1940 which were not nominated for Best Picture include Gunga Din, Destry Rides Again and The Women.

During the 1940s, the wins for unambiguously female-centered films started with Gone With the Wind and moved on to Rebecca and Mrs. Miniver. Best Picture winners with female co-leads include How Green Was My Valley, Casablanca and A Gentleman’s Agreement. The Best Days of Our Lives is an ensemble headlined by actress Myrna Loy, while second billing in The Lost Weekend went to Jane Wyman. Of course, in those days the movies were almost exclusively written, directed and especially produced by white men.

1950

Best Picture Nominees: All the King’s Men, Battleground, The Heiress, A Letter to Three Wives, Twelve O’Clock High

Clearly the golden age has passed (though several of these films are still well known). This group features the rise and fall of a politician, a brutal war film, the failed love story of a plain rich girl, a romantic drama about women and cheating husbands, and the story of a WW2 bombing group. Two of the five films have female main characters; the winner, All the King’s Men, has significant female roles, while Battleground has only one woman in it, and Twelve O’Clock High none. We can see the tightening of genre here — two stories of disappointed love, a political cautionary tale and two war flicks. These stories speak to the loss of innocence and all bear the same dark threads of disillusionment and brutality. For the first time, the overwhelming box office smash of the year (romantic biblical epic Samson and Delilah) isn’t invited to the party. (Samson and Delilah took in more than five times the amount of its closest competitor, Battleground!).

All five nominees do appear in the box office top ten, however. Overlooked releases that year include the classic comedy Adam’s Rib, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, The Fountainhead, the musical On the Town, Sands of Iwo Jima and The Third Man. Fun fact: Olivia De Havilland takes home best actress, ten years after her sister Vivien Leigh did the same for Gone With the Wind.

As before, we have all white male directors and almost exclusively white casts, with two actors of color — Jose Ferrer and Ethel Waters — receiving nominations, and Ferrer taking home a win. The coming decade brings many firsts and an increase in visibility: in 1954, Dorothy Dandridge becomes the first black actress nominated for Best Actress, and in 1958, Sydney Portier becomes the first black man to be nominated for Best Actor. Sessue Hayakawa becomes the first Asian man to be nominated for an acting award, Misohi Yimeki becomes the first Asian American to win an acting award, and there are four nods for Latinx actors, including two wins for Anthony Quinn.

As to later winners in the 1950s, we have All About Eve with a clear female protagonist (maybe even two!) and female co-leads in Gigi, From Here to Eternity and arguably, if you squint really hard, in An American in Paris.

1960

Best Picture Nominees: Anatomy of a Murder, Ben-Hur, Diary of Anne Frank, The Nun’s Story, Room at the Top

Okay, the classics are back again! I’d imagine most people have heard of three out of these five. A noir courtroom drama; a biblical-style epic of ambition, love and vengeance; the famous story of a young Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis; a nun who works as a nurse and struggles to subordinate her will to that of her order; and a romantic drama that follows the entanglement of ambitious young man and two different women. Again, mostly white casts (though A Nun’s Story spends some time in Africa) and all white male directors. Two movies have female main characters, and the other three all feature significant female supporting roles. Again, one black actress (Juanita Moore) is nominated for an acting role.

Only three of the best picture nominees appear in the top ten box office for the year, a significant change, although best picture winner Ben-Hur is also the box office champ. Overlooked classics from that year include Some Like It Hot, North By Northwest, The Shaggy Dog, Suddenly, Last Summer, The 400 Blows, Gidget, Hiroshima Mon Amour, Our Man in Havanna, Porgy and Bess and Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, many of which have stood the test of time as well or better than the above five.

Later in the 60s, Sydney Portier becomes the first African American to win lead actor for 1963’s Lilies of the Field; his is one of only three black acting nominations in the entire decade. Rita Moreno becomes the first Latina winner. Hiroshi Teshigahara of Japan becomes the first Asian man to be nominated for direction.

My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music mark the two female-centered films that won Best Picture in this decade, with a third musical, West Side Story, providing a co-lead. Starting in the 60s, African Americans almost abruptly began to pick up nominations in the categories where they remain the most represented: score and song.

1970

Best Picture Nominees: Anne of a Thousand Days, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Hello, Dolly!, Midnight Cowboy, Z

Audrey Hepburn gives way to Liza Minelli and Jane Fonda, and in comes a new sort of film. Instead of mysteries and melodramas we have a bloody historical drama, a witty Western adventure with a little comic flare, an effervescent musical romance, a darkly satirical political thriller and the only x-rated Best Picture winner ever, the friendship and violent struggles of a con-man and a prostitute. Just one of the five has a clear female lead, another male and female co-leads, though the other three films do feature some roles for women. This slate, like 2020, features a foreign film in Best Picture and its (male) director in Directing, as well as a single nomination for Rupert Crosse, the first African American nominated for Supporting Actor.

Well-known films that missed out on nominations in the 1970 race: Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, Easy Rider, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, True Grit, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Alice’s Restaurant, The Wild Bunch, and another version of Goodbye, Mr. Chips.

The decade of the 1970s will eventually bring us the first female directing nominee, Italy’s Lina Wertmuller for Seven Beauties, as well as five nominations for African American lead actors and actresses. If you consider Nurse Ratched to be a main character in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (I don’t particularly, though she did win Best Actress), then there are two Best Picture winners in the 1970s with women as protagonists. The other — the one possibly woman-centered movie — is Annie Hall. (Of course, the movie is famous for Woody Allen’s character, not Diane Keaton’s, breaking the fourth wall by addressing the camera.)

1980

Best Picture Nominees: All That Jazz, Apocalypse Now, Breaking Away, Kramer vs. Kramer, Norma Rae

1979 brought us another largely dark slate: a musical about the death of a womanizing alcoholic director, a war drama about a lawless soldier trying to make himself into a king, a father losing his son in a divorce classic, a complicated union drama with emotional and romantic entanglements, and the outlier, the uplifting coming-of-age story of four teens racing bicycles. As with the previous decade, we see the vision for women narrowing: only Norma Rae is the only one of the five about a woman, though All That Jazz and Kramer vs. Kramer have substantial female supporting roles. How sad is it that?

Only two of these movies made the box office top ten, another pattern we can see bearing out as the studio system disappears. Notable films that were passed over by Oscar: Alien, The Amityville Horror, Being There, Dracula, The Black Stallion, Rocky 2, The Muppet Movie, 10, The Jerk, and Monty Python’s The Life of Brian.

No woman is nominated for direction in the entire decade of the 1980s, but the first Latino and another Asian man are. Haing Ngor wins supporting actor, and something like 12 other people of color are nominated. The ’80s also saw the first movie with an African American producer nominated for Best Picture — Quincy Jones for The Color Purple, a literary adaptation about the lives of African American women.

In the ten years prior to the 1990 awards, there were 3 Best Picture winners with female leads or co-leads, all of which fit the stereotype of an “important” woman’s movie — Out of Africa, Terms of Endearment, and Ordinary People. Emotional, dealing with the character’s love lives, talking about one’s feelings.

1990

Best Picture Nominees: Born on the Fourth of July, Dead Poets Society, Driving Miss Daisy, Field of Dreams, My Left Foot

Here we have the story of a soldier turned anti-war activist, a disabled man who becomes a successful writer; a coming-of-age tale about inspirational teacher; the whimsical, magic realist tale of a man who hears voices and creates a baseball field for ghosts; and a buddy comedy about a white woman and her black chauffeur. The movies are largely set in the past. One of the five features a female co-lead, and the rest are all about men.

Yes, this year has five white male directors, but the acting slates continue their mild improvement: this time two of the nominees are people of color. Morgan Freeman is nominated for lead actor, and Denzel Washington actually wins supporting actor.

This is the year that got me really interested in tracking the Oscars and in indie film, thanks in large part to Daniel Day Lewis’ magnetic performance in My Left Foot. Of course, the prevalence of indie film means that movies the public loves and sees continue to decline: only 2 of these films made the box office top ten (Dead Poets Society and Born on the Fourth of July). Classic 1989 releases ignored by Oscar include Say Anything, Batman, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, The Little Mermaid, When Harry Met Sally, sex, lies and videotape, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Henry V, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation and Steel Magnolias.

During the 1990s, Jane Campion becomes the second woman nominated for direction. 14 actors of color appear on Oscar’s shortlist out of 200 possible chances. Not one was from The Joy Luck Club, a well-reviewed, sweeping literary adaptation about Chinese-American daughters and their immigrant mothers, widely heralded as the first American movie with an all Asian cast.

Also across the 90s, five movies won Best Picture that had female leads or co-leads — Shakespeare in Love, Titanic, The English Patient, Silence of the Lambs, and Driving Miss Daisy. Shakespeare’s shocking win over Saving Private Ryan remains controversial, and is often attributed to the machinations of master Oscar strategist, Harvey Weinstein. The first ever African American was nominated for Best Director — John Singleton for Boys in the Hood. The film itself was not nominated for Best Picture.

2000

Best Picture Nominees: American Beauty, Ciderhouse Rules, The Green Mile, The Insider, The Sixth Sense

And here it is. All five nominees have male protagonists. Unequally distributed among these five films there are maybe five meaty supporting roles for women, but largely, these are stories of men’s experiences. All five are movies I like, but the trend should be clear by now: stories about women are marginalized. Are they no longer being made, or are they being passed over? Of the films, one is a supernatural fantasy, one is a true story about a courageous whistleblower, one’s a prison melodrama, and all five really are about men who buck societal norms to find themselves. Big-name films that Oscar chose not to celebrate include Being John Malkovich, The Phantom Menace, The End of the Affair, Boys Don’t Cry, The Talented Mr. Ripley, All About My Mother, The Matrix, Magnolia, Angela’s Ashes and Toy Story 2.

Ten years into my love affair with Oscar, I became truly aware of the imbalance between movies critics loved when they reviewed them and the ones they honored at the end of the year. The witty Oscar Wilde adaptation An Ideal Husband and David Mamet’s moving historical drama The Winslow Boy, two spectacular costume dramas starring women, were fawned over by critics when they debuted and completely ignored come awards season. Why didn’t either movie have any heat? Why were they passed over? At the time, I wondered if this was because both movies came out during the summer, victim’s of Hollywood’s notoriously short attention span. Revolutionary queer films like The Talented Mr. Ripley and Boys Don’t Cry got nominations for acting, as did a spectacular exploration of faith, sex, and morality, The End of the Affair, but again were all snubbed for Best Picture. There were theatrical hits, and substantial indie dramas that told women’s stories, diverse stories. Why did they get left out in favor of movies that the critics had liked much less? As time goes on, the omissions make a pattern, and it becomes harder and harder to claim, “well, maybe those were just the best that year.”

Other numbers are holding steady — two of the acting nominees are people of color — Denzel Washington again, and Michael Clarke Duncan. Again, two of the BP nominees are in the box office top ten. One of the five male directing nominees is M. Night Shyamalan, who is of South East Indian descent.

This decade saw the first and only African American woman win best actress, Halle Berry for Monster’s Ball. In fact, it brought a comparative flood of nominees of color, somewhere in the vicinity of 29 nominees and 7 winners. In 2004, Sofia Coppola became the third woman nominated as a director for the elegant Lost in Translation, which follows a thoughtful young married woman wandering Tokyo with an older man; they form a deep, emotional bond but don’t cross the line into an affair. The older man is nominated for an Oscar; the beautiful young woman is not (and wasn’t until this year).

Brazilian director Fernando Meirelles received a directing nomination for City of God; Alejandro González Iñárritu begins the incursion of the so-called Three Amigos into AMPAS’s world with his work for Babel; a few years earlier, he directed Naomi Watts and Benecio Del Toro to acting nominations in 21 Grams. Hong Kong’s Ang Lee was nominated twice, and in 2005 because the first person of color to win Best Director. His film, the doomed gay romance Brokeback Mountain, lost Best Picture. Slumdog Millionaire, at once gritty and optimistic, won.

Million Dollar Baby (2005) and Chicago (2003) were the only Best Picture winners this decade to have female protagonists; the two films featured a boxer who was virtually the only woman in the film, and a set of singing female murderers.

2010

Best Picture Nominees: Avatar, The Blind Side, District 9, An Education, The Hurt Locker, Inglourious Basterds, Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ By Sapphire, A Serious Man, Up, Up in the Air

What a change this slate made from our last look. We have a largely CG sci-fi blockbuster, a family drama about a black football star and the white woman who adopts him, a South African dystopian sci-fi alien tale explaining the ugliness of prejudice, a British drama about a promising but naive high school student targeted by a predatory older man, a indie flick about the emotional isolation of military bomb squad members, a highly stylized alternate history about an assassination squad working to take out Hitler, the dark and gritty story of a black teen overcoming years of physical and sexual abuse, the story of a middle-aged man whose life is falling apart, the story of an old man whose life is falling apart (except it’s a brilliant cartoon and instead of grumping about it, he goes on a fantastical adventure), and a workplace comedy about a middle-aged man who realizes that yes, his life is not what he thought it was going to be.

Avatar and Up are the only movies in the box office top ten. Beginning in 2010, however, AMPAS expanded the Best Picture category from 5 nominees to 10, in an attempt to woo back viewers who were abandoning the show as it abandoned movies that they’d actually seen. This change was quickly followed by our current system, which allows for somewhere between 5 and 10 Best Picture nominees based on a preferential ballot. In practical terms, this almost always results in 9 nominees.

Kathryn Bigelow made a tiny movie called The Hurt Locker about adrenaline-addicted soldiers, a film with only one woman in it, playing the main character’s wife. She received a Best Director nomination, and won. It probably didn’t hurt that she was up against her notoriously arrogant ex-husband, Oscar-winning director James Cameron, who helmed a motion capture flick that obliterated the box office, the sort of successful movie that Hollywood “artistes” loathe. Giving Best Picture to The Hurt Locker, which made 32 million dollars world wide, over Avatar, which made 2.8 billion and is currently launching a theme park and a host of sequels, is as clear a way as any of sticking it to the man. Of course, The Hurt Locker also reinforced common themes about masculinity much appreciated by AMPAS voters, which the environmentally focused “white man goes native” Avatar did not. In other words, it looked like change, but was it?

One other woman — Greta Gerwig — was nominated for best director in the entire decade. To this date, no woman has been nominated twice, despite both Gerwig and Bigelow making high profile films (Little Women and Zero Dark Thirty) that were nominated for Best Picture. For that matter, it’s a strange quirk of Oscar that of the 35 times a black woman has received acting Oscar nomination, only three (Whoopi Goldberg, Viola Davis and Octavia Spencer) have been nominated more than once, and only Spencer has been nominated after winning her award. The odds of repeat Oscar love are slightly better for the men: Sydney Poitier, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, Jamie Foxx, Djimon Honsou and Mahershala Ali have been nominated multiple times.

Two movies on the 2010 slate had black producers and major characters, The Blind Side and Precious. Precious’ Lee Daniels becomes the second African-American man nominated for Best Director; later in this decade he’s followed by director Steve McQueen (who was passed over for the win even though his film, 12 Years a Slave, took Best Picture), Barry Jenkins (who was passed over even though his film, Moonlight, shocked prognosticators to win Best Picture), Jordan Peele and Spike Lee. Moonlight told the story of a black drug dealer who conceals his sexuality in order to preserve a macho facade; ironically, Mahershala Ali won an Oscar for playing the boy’s (straight) mentor, while none of the many brilliant actors who played gay characters in the film received even a nomination. Acclaimed director Ryan Coogler missed out on a nomination for his box office-topping work in Black Panther, even though the film itself received a Best Picture nomination.

AMPAS voters did, however, fall resolutely in love with the films of the Three Amigos, awarding them five statuettes in a row. Alfonso Cuarón wins his directing Oscar for the astonishing technical virtuosity of Gravity, but loses Best Picture to 12 Years a Slave. Iñárritu is nominated as the director of hyper-masculine films Birdman and The Revenant, and wins both times. Guillermo del Toro, whose gruesome historical fairy tale Pan’s Labyrinth won Foreign Film in the 2000s, picks up the next directing Oscar for The Shape of Water, and then Cuarón takes another directing award for his ode to his childhood and his nanny, Roma, which loses Best Picture to Green Book. Ang Lee extended the same winless streak as Cuarón; he won the directing Oscar for 2012’s Life of Pi, after the surprise exclusion of Best Picture winner Argo‘s director Ben Affleck, giving him a second Director win without the corresponding Best Picture statuette. Ava DuVernay was less lucky — her moving civil rights drama Selma was nominated for Best Picture while she was snubbed. She would have been the first African American woman to be nominated as a director.

In the 2010s, about 22 of a possible 200 acting nominations went to people of color, down from the previous decade. (I say “about” in case I’m missing someone, and also because of some ambiguity: should Berenice Bejo be considered a person of color because she’s French Argentinian? What about Rami Malek, who’s of Egyptian descent?) Never as successful at gaining AMPAS attention as their black and Latinx colleagues, the last Asian to receive an acting nomination was Rinko Kikuchi for 2006’s Babel. That’s right. Not one in the entire decade. African Americans scored 6 acting wins, all in the supporting categories, 4 of those for supporting actress.

As more and more outspoken people noticed and publicized the relative dearth of contenders of color, the Oscars were plagued by the #Oscarsowhite hashtag, and accommodates were made to try to remedy the matter, including broadening the voting pool and inviting women and people of color to become a slightly larger percentage of that pool. An attempt – quickly shot down – was also made to combat the telecast’s falling ratings; AMPAS hoped in 2020 to include a “Best Popular Film” category, allowing it to at once honor and also ghetto-ize the sort of box office success that used to be an Oscar mainstay but has since (especially in the age of the Superhero) fallen into disrepute.

2018’s winner, science fiction romantic adventure The Shape of Water was the only Best Picture winner in the decade with a female lead character. Ironically, several films with female protagonists led the box office in the 2010s — Frozen, The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi. Other box office smashes with female leads include Rogue One, Beauty and the Beast, Wonder Woman, Finding Dory, Zootopia, Maleficent, Alice in Wonderland, The Twilight Saga films, Gravity and all four highly acclaimed Hunger Games films. Gravity was the only one of these nominated for Best Picture; it won seven Oscars, but lost the Best Picture race. No crew member who won awards for it was a women.

2020

Best Picture Nominees: 1917, Ford v. Ferrari, The Irishman, Jojo Rabbit, Joker, Little Women, Marriage Story, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, Parasite

So here we’ve got a searing WW1 trenches saga, the story of a self-destructive race car driver trying to get his life together, the life story of a hitman, a Nazi tragicomedy from New Zealand, an anti-hero comic book story about a middle-aged sociopath whose life is falling apart (except hey, he loves it), a coming-of-age literary classic, the anatomy of a divorce, a story about a middle-aged man whose life is falling apart, and a creepy, original thriller about class and power structures.

That shakes out to one story with a female protagonist, one decently gender-balanced ensemble drama from South Korea (a first), and one story with male and female leads. All six other films are stories of men. Jojo Rabbit is the only one of the six with a meaty female supporting role in it (actually two). Joker is the only nominee that made the box office top ten.

Obviously it’s too early to name anything a classic, but alternative titles that Oscar could have picked are legion and far more diverse: critically acclaimed movies like A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, The Farewell, Booksmart, Knives Out, Us, Judy, Harriet, Hustlers, Where’d You Go, Bernadette, Bombshell, Dolemite is My Name, Queen and Slim, Just Mercy, or The Two Popes, or well-reviewed box office smashes like Rocketman, Captain Marvel, Spider-Man: Far From Home, The Lion King, Frozen 2 and Toy Story 4. Women who directed movies that are as well-reviewed, and in many cases better-reviewed than the movies that did get nominated, include not just Greta Gerwig, but also Lulu Wang, Olivia Wilde, Kasi Lemmons, Lorene Scafaria, Melina Matsoukas, Marielle Heller, Anna Boden and Jennifer Lee.

***

What does all this history say? That the women doing good work are out there. That as women make more strides in life, and win more political victories, they are still marginalized from America’s big screen story-telling — and when they make strides, those strides are often ignored. That the 1940s, counter-intuitively, were the heyday of films about women marketed to women, and films about women seen by all. As home entertainment gets more sophisticated, conventional wisdom has it that audiences will only venture to the multiplex for spectacle, and spectacle means explosions and/or superheroes, and those things mean men. Oscar doesn’t like superhero movies or action comedies — but it does love other forms of what it perceives to be masculinity. And it seems to be clinging to those outmoded forms of masculinity, fingers dug in knuckle deep.

More and more, we see that Oscar is codifying a type, and that type centers on violent white men. That’s what AMPAS sees as a serious film. Gangsters, mobsters, anti-heroes, mavericks, con men, Nazis. If you’re a genre film, if you’re a gentle film, if you’re a horror film, if you’re a romance or romantic comedy, if you’re anything but a violent drama or a pitch black comedy, Oscar no longer wants you. Good luck even getting made today if you’re a straight-up romantic comedy, or a romance that’s not aiming for the Hallmark Channel — and there it is. It’s hard to get movies made about the experiences of people of color or women. It’s still hard to get a directing gig if you’re a woman. When your work does get made – maybe by female movie stars starting companies to produce great stories for each other – Oscar has real trouble voting for it for one of the big categories. Sure, you might get lead actress, but Best Picture? Director? Naw.

Seriously, check it out.

The more strides women make behind the scenes, the fewer movies about them get nominated. It’s far easier than it was to make movies about people of color and the LGBTQ community. Female directors are definitely more common than they were 20 or even 10 years ago. Male directors of color have made enormous strides. But AMPAS is still redefining what’s “best” to exclude them. And I would say it’s harder to make a movie starring a woman than it was 20 years ago — absurdly difficult, especially when you realize that 70 or 80 years ago, gender parity was the box office norm.

In other words, it’s not just about what the best films or performances are in a given year. All of that’s subjective. It’s about what, through its changing history, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences shows that it values.

Let’s look at the 80s and 90s, when Oscars broadcast ratings were good, when people actually watched the movies that got nominated for Best Picture. You saw steretypically woman-oriented movies nominated like Pretty Woman, Working Girl, Steel Magnolia’s, Tootsie, Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Fugitive, Shakespeare in Love, and so many more. If you look at the past decade, here are the “romantic” movies you see: A Star is Born, in which one character ends up dead, LaLa Land, a light and fluffy seeming musical where the couple breaks up, The Theory of Everything, where the couple divorces, Her, a man’s romance with his Alexa, Silver Linings Playbook, which is just as much about mental illness, Amour, where the husband murders his ailing wife, Call Me By Your Name, a gay coming of age drama in which one of the lovers slinks back into the closet. Think about that grim list. It Happened One Night they are not. Of course’s there’s always The Shape of Water, in which Guillermo Del Toro reinvents The Creature from the Black Lagoon as a love story; a romance where the two strange soulmates can’t even speak to each other.

Not that romance is all that Oscar excludes, of course. Why have straight up movies about human emotions – about love, about family – become so unacceptable, whether comedic or dramatic? Horror, camp, action, fantasy – how could they say something meaningful about the human condition? What about movies that are just brilliant at being fun? No, AMPAS tells us, the only good is “serious,” and you can’t really be serious if you’re not gloomy. Happy is not acceptable. And even if you bring the unhappiness, so vividly on display in Judy, one of this year’s best films, it doesn’t mean as much if it’s simply a woman struggling. Now, if Judy Garland had started shooting up the audiences at her London shows, this race might have been different. It’s like AMPAS fears any emotion that’s not a blood lust.

This year Oscar’s favorites are shockingly soulless. The Irishman, Once Upon a Time, Joker – this year’s most nominated films all center around sociopaths, men who either show no remorse or – worse – find joyful purpose in murder. Morality is irrelevant. Does this express some sort of impotence, some cultural despair still bleeding out from Trump’s election and impeachment? Little Women – a film about sisters who yes, happen to have romantic entanglements – tells us that life is about putting away one’s anger and getting things done, about doing true work rather than being bogged down in what we think we’re owed. About the struggle to make a better world, and how it wears on us, and how we have to learn to focus ourselves, sacrifice, make mistakes and accept criticism in order to move forward. Instead, Oscar chose to celebrate a violent response to nihilism; the world is crap, so you might as well be as bad you want.

It’s almost as if that’s what AMPAS is telling us as it fights to reassert control after every step forward. Of course Gerwig wasn’t nominated. She wrote it herself, in Little Women, in a scene where one sister declares that if she can’t be great, then she’s done with the struggle. Timothee Chalamet’s character suggests that the perception of greatness varies based on the whims of gatekeepers: “What women are allowed in the club of geniuses anyway?” Oscar seems to be insuring, more and more each year, that they never have a chance.

Fantastic, illuminating piece. I’m commenting on it in my blog post tonight. More people need to read this.

Thank you so much! I really appreciate the boost from a fellow (classic) movie fan.

I am also very skeptical about the S in Love controversy. It is a deeply feminist film, and it’s so well crafted, creative, and perfectly edited that it’s hard to understand the deep anger, especially since Saving Private Ryan is far from Spielberg’s best work.

What I feel like people forget is that at least most Oscar fans were really bored with Saving Private Ryan as a winner – as you say, it’s a terrific movie, but it suffers in comparison to Schindlers List, etc…, yet it was winning every pre-cursor award out there. I’m sure that fatigue is what enabled Moonlight to beat LaLa Land, as well. You think, well, I know X is going to win, but didn’t I enjoy Y more? Doesn’t it make a more meaningful statement? And then suddenly, it wins.

It’s funny you say that. I was just reading an article about how Oscar voters keep thinking they have to nominate films they don’t enjoy because serious films are somehow better. Shakespeare in Love is so much FUN. It’s a shame that entertainment isn’t considered a worthy metric, though it does explain why so few comedies ever get their due. And Shakespeare DOES really have some messages about women’s rights, about artistic inspiration, etc.–it just delivers them in a light way. I still use that “It’s a mystery” line to capture that feeling when you know a seemingly impossible task will get done and need to stop worrying about it:)

I definitely think that’s why Shakespeare in Love won, because it was enjoyable, back when enjoyable wasn’t so much of a dirty word. I think that’s why La La Land lost – because it was enjoyable but maybe not deep and definitely not a statement. And gosh but it’s ridiculous to say that entertainment shouldn’t be a factor in judging how good a movie is! AMPAS needs to be better about finding a happy medium.

[…] “Maybe Those Are Just the Best Movies This Year”: #WhiteMan’s Oscar in Context.… […]